Time for greater regional and global integration: the euro role

The international relations are navigating perilous waters of increasing conflicts and unprecedented uncertainty. As all crises, this represents both a risk and an opportunity, if one is ready to face the challenges.

The international economic and monetary system had already been evolving in the last few decades through increasing tensions and contradictions, which became more and more acute and difficult to sustain. Basically, interdependence was left to increase – both in terms of globalization of trade due to dispersed value chains and increasing capital mobility, in the context of a digital transition that allowed real-time capital movements – without providing the governance infrastructure to manage such worldwide interdependence.

The recent four major shocks that hit the global economy (Covid-19, with the upsetting of global value chains; Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the subsequent energy crisis; the resurgence of inflation, both cost-driven and speculation-induced; the advent of protectionism in the heart of the global economic system with the advent of Trump) are now exposing all the contradictions that have been accumulating since decades.

At least since 1997, when the USA (with the complacency of the IMF) frustrated the Japanese proposal for an Asian Monetary Fund (Masini 2024), a regional tool to avoid domino effects in the East-Asian currency crisis, while China was negotiating its accession to the WTO. Since then, we have seen a skyrocketing accumulation of reserves (in US Treasury bonds) as a cushion against potential sudden capital flights and the need to recur to the IMF, with its heavy conditional lending. Hence the growing of a paradox: savings from the rest of the world have been financing US expenditures, both investment and consumption. This paradox is particularly striking in the case of low-income countries, which were bound to buy $-denominated T-bonds for precautionary reasons, given their vulnerable financial position, instead of spending for growth and social protection.

Such paradox could survive only thanks to the credibility and recognized legitimacy of the dollar to play a hegemonic role; and of the US-denominated T-bond to be the safe asset par eccellence. Which could in turn rely on the US playing the role of guarantor of free trade and a stable currency and its function as de facto Lender of Last Resort (via the currency swaps of the FED) and Consumer of Last Resort of the US Federal Government during major systemic crises (as in 2008-09).

Attempts at fixing some flaws of the international monetary system with a new international monetary conference, a sort of Bretton Woods 2 (as was repeatedly called for in those years), based on overcoming the Triffin Dilemma (as the speech by the Governor of the People Bank of China Zhou made clear in March 2009) were frustrated by USA (and the whole G7).

Hence the emergence of the BRICS (June 2009), the multilateralization of the Chiang Mai Initiative and the establishment of a first-line regional safety net (2011) and the recent trans-national payment system in renminbi (2025).

Such evolution shows that we are heading towards a new bipolar world, with a weaponization of currencies and financial infrastructures that needs to be resisted, as a new confrontation between blocks would hinder the production of global public goods that are increasingly becoming crucial for the survival of humankind: decarbonization and the struggle against climate change, a peaceful resolution of conflicts, universal access to primary resources, regulation of the digital transition towards artificial intelligence and the new technologies, etc. All unanimously shared needs by the citizens of the world, that require global collective action.

Although these issues are usually left to top-level strategic games between a few major global players, we believe that the peculiar situation we are currently experiencing leaves some room for manoeuvre to bottom-up political action.

First, the emergence of awareness concerning the global nature of a few but key public goods opens the opportunity for a narrative pushing for the establishment of mechanisms and institutions for the provision of such global collective goods. Such narratives might serve to collect popular calls for more practical action, upscaling initiatives such as the Fridays for Future that emerged a few years ago and should not be wasted.

This would also enhance the possibility to strengthen the process towards multilateralism, through greater regional integration in all major areas of the world: Africa, Central and Latina America, South-East Asia, etc. All existing regional initiatives should be encouraged, with a few concrete proposals such as the establishment, for example, in both Africa and Central and Latin America, of regional safety nets, comparable to the one existing within the Chian Mai Initiative.

Secondly, the impossibility of the renminbi to be a genuine, alternative safe-asset to the USD-denominated T-bond, given its obscure capital market and poor transparency, provides an opportunity for the euro to acquire a greater role in international payments and reserves. This would require the completion of the banking union and single capital market, its increasing deepness and liquidity, on all yield/maturity combinations, and the increasing quantity of euro-denominated T-bonds, not fragmented in national issuers but centralized at the supranational level for high-quality and high-return investment projects. From this point of view, however smart, proposals to revive (Blanchard 2025) the blue-bond proposal (Delpla and Weizsäcker 2010) are not heading into the right direction, as they would only consolidate past debt, instead of facing the current challenges. We should also acknowledge here the resistance of national governments to allow trans-national mergers and acquisitions that would rationalize the banking system and make it more competitive in a global market.

This would require a political and intellectual shift away from standard economic policy orientation in Europe, as availability to lose part of its monetary sovereignty sacrificing domestic objectives to international needs would be necessary, possibly in cooperation with the other major global players, as well as issuing more supranational collective euro-denominated bonds for collective regional projects and playing the lender of last resort in case of global systemic crises.

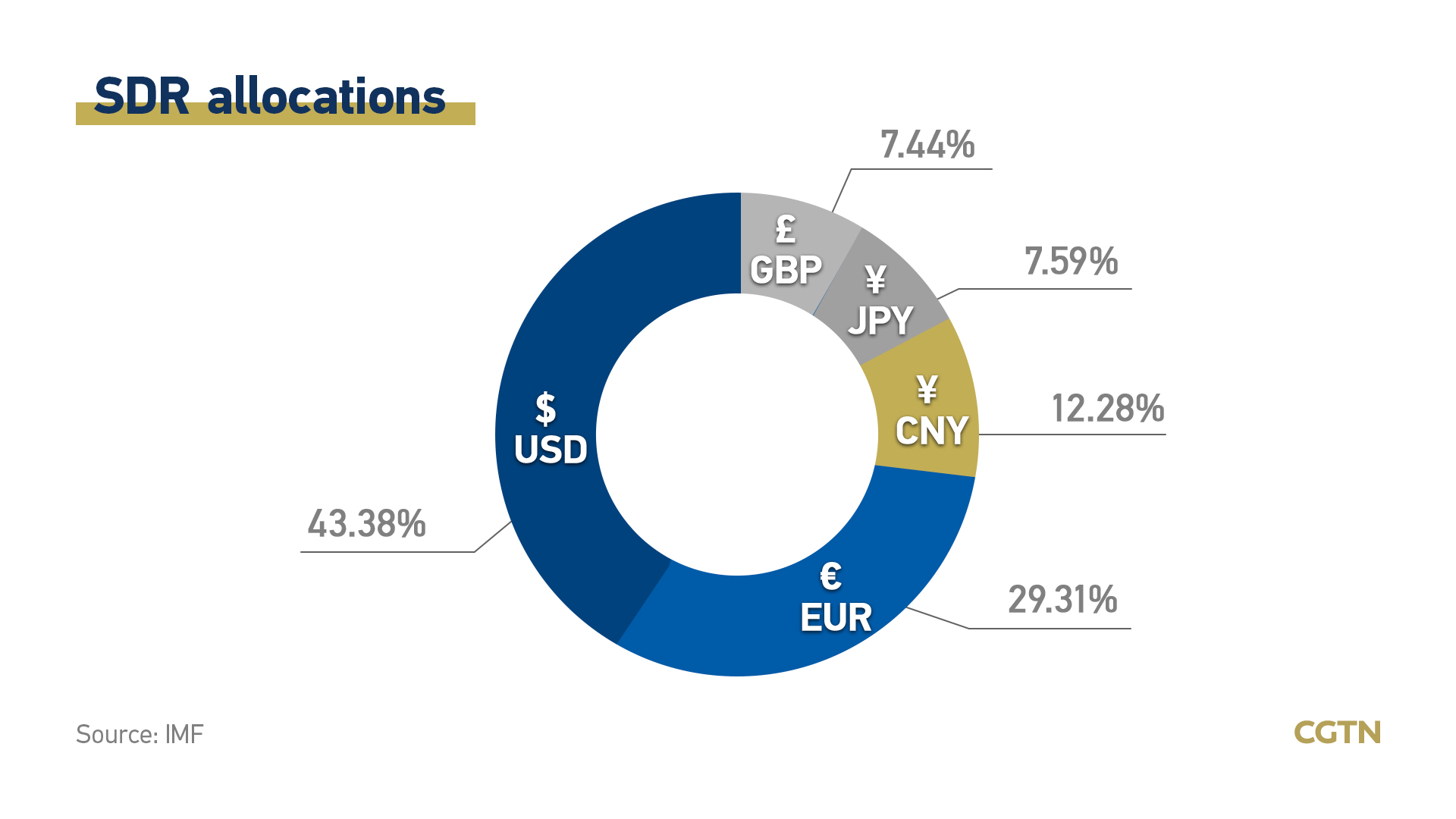

An increasing international role of the euro, though, should not aim to replace the dollar as a principal reserve currency in the world, with the risk of replicating the contradictions that have been characterizing the dollar hegemony; nor should we aim at a multi-currency system, that might bring about even greater financial instability. A greater role of the euro should only aim, in the short-term, at showing that an alternative to hegemonic stability is possible. While, in the medium-term, the objective should be enlarging the role of SDRs (the only multicurrency asset) as “principal reserve asset”, as the Articles of Agreement of

the International Monetary Fund state (art. XXII). This would require a collective responsibility to coordinate broad monetary policies between the major global players, both in normal times, to manage macroeconomic surveillance and financial stability, and open the possibility, in the middle-term, to a revision of the SDR basket allowing for accession of regional currencies and, in a longer-term, the eventual transformation of SDRs into a genuine supranational currency, not based on national ones, issued to finance global public goods.

We are now experiencing an extraordinary opportunity to struggle for: a strengthening of regional integration processes, especially in Europe, where a constitutional reform of the EU would increase its international actorness; and for a reform of the international monetary system to deliver on the provision of crucial global public goods in a multipolar, multilayered logic. As academics, think-tanks, and civil society organizations, we are all called to exploit such unprecedented window of opportunity; we should not miss it.

References

Blanchard O. 2025. Now is the time for Eurobonds: A specific proposal, Peterson Institute for International Economics, May 30, https://www.piie.com/blogs/realtime-economics/2025/now-time-eurobonds-specific-proposal.

Delpla J. and von Weizsäcker J. 2010. The Blue Bond Proposal, Bruegel Policy Brief, 3, May 6.

Masini F. 2024. Reappraising Japan’s proposal for an Asian Monetary Fund, Rivista di Studi Politici Internazionali, 91(3), 367-392.