Under the Trump administration, the issue of international trade returned forcefully to the center of public and political debate. Already during his first term, the president had implemented an aggressive trade policy based on the introduction of tariffs, justified by the need to reduce the American trade deficit. In the new electoral cycle, this approach has been further radicalized, despite the fact that its economic premises are deeply flawed by conceptual errors.

The irrelevance of the bilateral deficit

One of the fundamental assumptions of the Trumpian narrative is the focus on the bilateral trade deficit with individual countries or geographical areas—such as the EU, China, and Mexico, to name a few. However, this approach is economically unfounded. In a globalized economy, value chains are transnational: a single product may include components from a dozen different countries, making an imbalanced distribution of bilateral balances inevitable.

For example, a country might import components from country A, process them, and sell the finished product to country B. Therefore, the trade deficit with country A is a natural consequence of the production process, as is the surplus with country B. It is clear that complaining about the trade balance with country A is meaningless, as it is the prerequisite for producing and selling the finished product. Drawing a parallel with private companies, it would be as if a company did not want to owe anyone, implying that its suppliers must also be its end customers to achieve a balanced or positive trade balance with all counterparts.

Similarly, purely geographical reasons can explain structural bilateral deficits. Think of certain agricultural products that must be grown in specific geographical or climatic areas, such as coffee or exotic fruits. When the bilateral trade deficit is driven by products of this type, there is no reason why it should be eliminated.

In essence, in the absence of unfair trade practices like dumping or illegal subsidies (where the WTO rules already allow the introduction of countervailing duties), it makes no economic sense to place importance on the bilateral trade balance with individual countries.

A more accurate analysis: the overall trade balance

It makes more sense to analyze the overall trade balance (which we could define as the bilateral balance with the rest of the world). However, even in this case, the evaluation has to be done with caution. The idea that a trade deficit is inherently synonymous with a loss of national wealth is simplistic and misleading. It is wrongly argued that part of domestic demand is “lost” to foreign countries, generating a negative effect on the economy.

The reality is more complex. A trade deficit implies that the economy is consuming more than it produces, but if the labor market is at full employment or near it (as has been the case in the US in recent years), imports are the only way to satisfy an expanding domestic demand. In this context, the trade deficit is not a sign of weakness but, on the contrary, a physiological consequence of the strength of demand. In other words, in this situation, higher imports are the only way to fully meet the consumption needs of citizens.

Even more important, we must consider the flip side of the trade deficit, i.e. the related financial movements. Having a trade deficit means that the country is borrowing from the rest of the world. To understand why, consider, for example, an American company that imports a product from Europe. This transaction means that a certain amount of dollars ends up in the European economic system: typically, in the bank of the European exporting company, and from there possibly to other financial institutions or, ultimately, to the Central Bank. These dollars are then used to buy US government bonds or corporate bonds or stocks of American companies. Essentially, the condition for the United States to import products from Europe is that the European economic system is willing to finance the American one.

The consequence is that there is a fundamental macroeconomic link between the trade balance and domestic dynamics, expressed by the following accounting identity:

I = S + CA(−)

where I represents investments, S represents domestic savings, and CA(−) represents the current account deficit (which includes the trade deficit). This relationship shows that, in the presence of low domestic savings, a country can still support high levels of investment thanks to a current account deficit, i.e. due to a trade deficit. Returning to our example, the financial assets purchased by the European economic system enable the financing of real investments by the American system. In practice, a country finances its internal investments partly with its own savings and partly by borrowing from abroad; conversely, a country with a trade surplus uses its own savings partly to finance internal investments and partly to lend abroad.

In this sense, the trade deficit is the counterpart of an influx of foreign capital that finances domestic investments. In other words, the only way for a country to borrow from the rest of the world is through a trade deficit. So, if a country needs foreign capital to finance part of its public debt or corporate investments, it can do it only via a negative trade balance. Also from this second perspective, the presence of a trade deficit cannot obviously be considered, as President Trump has put it, as a theft by foreign countries. On the contrary, America’s technological superiority, which drives its economic growth, was achieved thanks to significant investments in research and development made possible, in part, by foreign financing.

After all, the United States has recorded trade deficits for decades, yet continues to grow at a faster rate than many export-oriented economies, proving that the trade deficit is not itself a constraint on economic growth.

The question of foreign debt

The real problem, as is often the case in economics, arises when we move from the short-term to the medium and long-run: a sustained trade deficit over many years results in the progressive accumulation of debt to foreign countries.

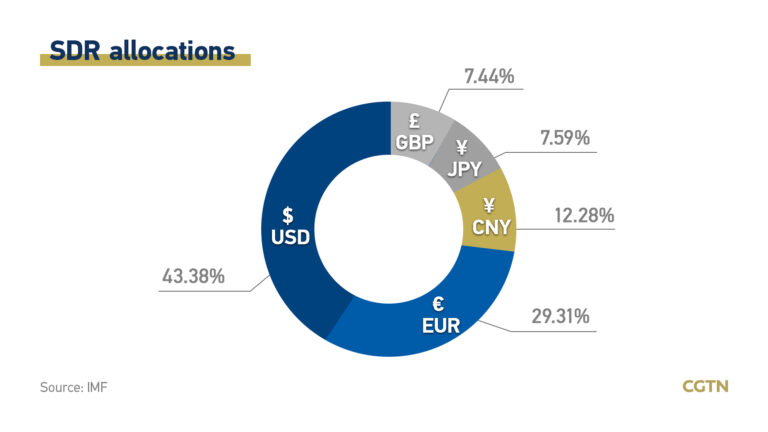

In the case of the United States, the ability to accumulate foreign debt has so far been supported by two main factors: the credibility of the American economic and financial system and the so-called “exorbitant privilege” of the dollar, which continues to be the global reserve currency. This gives the US a margin of maneuver that no other country possesses, as the demand for financial assets denominated in dollars is very high, allowing the US to finance its growing foreign debt. However, if foreign debt becomes excessive, it could result in a loss of confidence in the ability of the American system to support such debt. Essentially, the same reasoning applies to any form of indebtedness: it allows for profitable investments, but it is necessary not to accumulate too much over time. Hence the need, raised by several economists well before Trump’s arrival, to limit foreign debt to avoid what is defined a “balance of payments crisis”.

Reducing the foreign debt, but not with tariffs

So, it makes sense to want to reduce net foreign debt, but certainly not for the misleading and ideological reasons put forward by the Trump administration. But using tariffs to achieve this goal is economically inefficient: empirical studies show that the cost of tariffs falls largely on domestic businesses and consumers due to the higher prices they bring. Moreover, using tariffs results in an economic loss due to decreased competition between companies and a significant global cost related to reduced international trade and heightened tensions between groups of countries.

Furthermore, it is well known that the US economy has a structural excess of consumption compared to other advanced economies. This excess is one of the main causes of the trade deficit. And yet, a natural candidate to rebalance the situation would be obvious: a reduction in the massive US public spending, which currently fuels consumption and compresses national savings. Returning to the macroeconomic identity I = S + CA(−), it is clear that a compression of savings, due to excessive fiscal deficits, enlarges the trade deficit. In essence, attempting to rebalance the trade balance through tariffs will likely result in higher prices and reduced consumption, investment, and production; it would be far more efficient to achieve a rebalancing by reducing the reckless public deficit, which would allow for a smoother decline in consumption and would free up savings to finance investments.

The ideas behind Trumponomics

The Chairman of Donald Trump’s Council of Economic Advisers is a young, so far unknown economist, Stephen Miran. His articles and speeches are opposed to the views of almost all American economists, but it is worth considering his perspective in this context. The central point of his thinking is that the aforementioned “exorbitant privilege” of the dollar actually harms the average American citizen; the reason is that the structural demand for dollars causes the dollar to appreciate, making it more expensive than economic fundamentals would suggest, thus damaging the American economy. The solutions proposed by Miran are varied, ranging from the absurd (forcing foreign-held US government bonds to be converted into perpetual bonds with no interest) to the now popular imposition of tariffs.

As previously mentioned, the idea that issuing the global reserve currency is a harm to the US economy is strongly rejected by almost all economists. While it is true that the dollar tends to have a higher value, one cannot forget the numerous advantages of having the world’s reserve currency: lower interest rates for the government and businesses, easier access to credit, use of your own currency in international trade, control over global financial transactions and consequently control over the international monetary system, and so on. It is therefore widely understood that the “exorbitant privilege” is actually advantageous for the American economic system as a whole.

Additionally, the numerous economic contradictions of the Trump administration should be noted. Scott Bessent, the US Treasury Secretary, stated that tariffs would strengthen the dollar, leading to a reduction in the prices of imports (in terms of dollars), thus helping to contain the inflationary effects of the tariffs themselves. In short, he claimed that the appreciation of the dollar would benefit the economy, the exact opposite of Miran’s theory (incidentally, so far in 2025, the dollar has depreciated by more than 10% against other major currencies). But the inconsistencies don’t stop there. President Trump declared that fighting inflation is a primary goal of his administration, yet he has repeatedly attacked Jerome Powell, which undermines the independence and credibility of the Federal Reserve, a crucial requirement for controlling inflation. Moreover, Trump has repeatedly called for interest rate cuts by the Fed, yet he also fired the head of the Bureau of Labor Statistics for providing “false data” (without any proof) on the weakening labor market; however, it is precisely the weakening of the labor market that might prompt a reduction in interest rates. Also, there is the already discussed contradiction between pursuing a reduction in the trade deficit while massively expanding the public spending.

In short, we cannot avoid noting that the economic policies of the American administration are confused, contradictory, and often dangerous.

The European Union and the role of the Commission

On the European side, the recent agreement reached between Ursula von der Leyen and Trump has sparked controversy in some national political circles. However, it is possible to make some deeper considerations.

From an institutional perspective, it is important to highlight that the negotiation was conducted by the President of the European Commission, confirming the EU’s exclusive competence in trade matters. The individual member states, even the largest ones, implicitly recognized their marginality by delegating trade representation to the Commission. This is an important step toward greater federal integration and the recognition of the European Union as the single entity enabled to act in certain circumstances.

This recognition is independent of the merits of the deal itself, which can legitimately be subject to political evaluation. Nonetheless, it is hard to imagine how the Commission could have achieved better results. The Union had a clear interest in avoiding a total rupture with the United States, and the current geopolitical context—with the war in Ukraine and the need to maintain the American military commitment in Europe—made the compromise even more necessary. One must also bear in mind that the agreement reached in Scotland does not mark the end of negotiations, as several details still need to be clarified; meaning the Commission will have the opportunity to abandon caution if the Trump administration’s demands become too burdensome.

Finally, once again, it is inevitable to notice how European national politicians seek to blame the EU for their responsibilities. Within the single market, there are still non-tariff barriers and inefficiencies that generate significant economic losses. According to some estimates by the International Monetary Fund, the full integration of the single market could generate annual economic benefits amounting to hundreds of billions of euros. The Draghi Report clearly outlined the way forward, but (for now) it has not been followed up due to the inertia of national governments. In conclusion, while the debate continues on the effects of American protectionist policies and the damage stemming from the supposedly poor agreement reached by Ursula von der Leyen, individual European countries would do well to also look at their own structural inefficiencies: a more integrated and competitive European Union would be the best way to respond, both economically and politically, to the challenges posed by the return of global protectionism.