The wars just over the EU borders have brought back into focus the most demonic and evil form of power, i.e. military force. EU citizens have not been subjected to this kind of power for 80 years. Not because Italians, French, Germans and other Europeans have become pacifists or better people, but because a particular historical process has developed in this part of the world, resulting in common institutions (the European Union) that have made war between Europeans impossible, actually unthinkable. This is not common knowledge, because people believe new things only when they are well-established, as Machiavelli said.

On February 24, 2022, a war started that aimed to change the world – for the worse. There were three basic reasons behind the Russian aggression: the determination that Ukraine should return to the “Russian world” (Russkij mir); the removal of individual EU countries from American hegemony, and the establishment of a new world order with a reduction in the importance of the West and the return of Russia to a key role in the world. [1]

On October 7, 2023, yet another war began in the Middle East, between two peoples and two nationalist aspirations, one that has already become a state (Israel), the other seeking statehood (Palestine/Hamas). Each claims the identical territory: the conflict has inevitably become radicalized. Each has its own system of international alliances: there is a risk that the conflict will spread to other states.

In the area of the Pacific, the cold war between China and the United States has given rise to tensions which are even more dangerous for world peace: there, attempts are being made to set up a new world order based on two superpowers, which is dangerous, among other reasons, because it is outdated and unrealistic. Africa is troubled by endless conflicts, prey to old and new forms of imperialism, torn between various nationalist movements and in search of a difficult path to continental unity.

In short, nationalism is rearing its head again, in Europe and the world.

Clash of opposing principles.

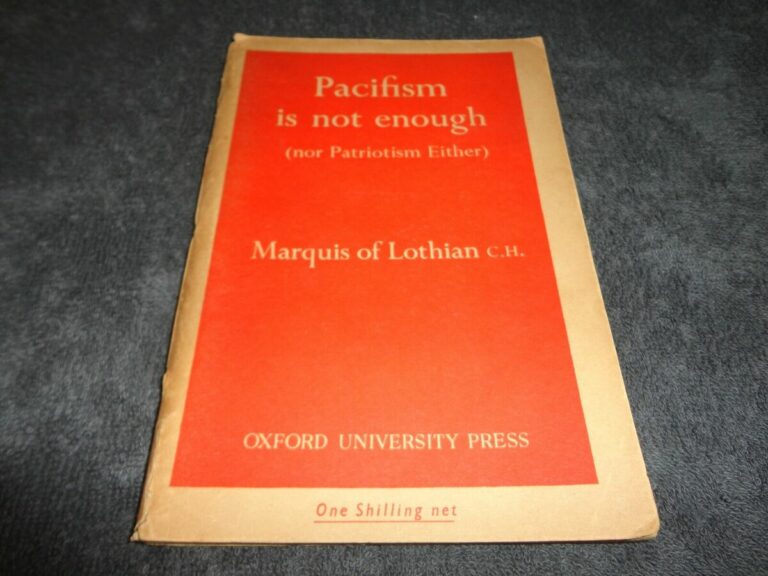

We are faced with a contradiction that is even more extreme now than it was in the past. Globalisation tends to make states interdependent, economically, socially and culturally, thus uniting the world. However, the world continues to be governed by the principle according to which each state thinks of itself as ‘independent’ and fully sovereign, even for issues common to all, such as the environment, health, trade, digital, technology, social and territorial imbalances, migration etc. The term ‘sovereignty’ no longer applies in today’s world, which is interdependent in its essential needs.[2] A fully sovereign state inevitably belligerently seeks its own “living space” if there are no supranational institutions to govern its relations. Thus, Hitler’s lebensraum returns today in Putin’s Russkij mir, both ideologies of nation-states with an imperialist mission. This is why pacifism, in itself, is not enough, because it does not alter the (violent) nature of relations between states which think and act as if they were fully sovereign, waging war on each other as the highest expression of the sovereignty they lay claim to.[3]

A little over two centuries ago, Kant proposed a new direction based on reason. He suggested that just as “savage man was forced to renounce his brutal freedom and seek peace and security in a legal constitution” states need to “leave the illegal state of barbarism and enter into a federation of peoples, in which each state, even the smallest, can hope for its security and the safeguarding of its rights not from its own force or legal assessments, but only from this great federation of peoples (Völkerbund), from collective strength and deliberations according to the laws of the common will.” [4]

Kant’s indications go further: without supranational federal institutions to guarantee peace among states, the fundamental values of freedom, justice and equality cannot be fully realized; not only among peoples, but also within each individual state; in war, states drastically limit the internal space for freedom and democracy.

Kant is prophetic. The destructive potential of nuclear weapons means that the problem of overcoming the division into sovereign states can no longer be regarded as a theoretical question of an enlightened mind, but must stand as the political goal of our time. To live with war involves accepting the idea of the total degradation of morality and the ultimate demise of the human species. It is this situation, then, that, according to Kant, will drive states “to do what reason…might have suggested: that is, to leave behind the illegal state of barbarism and enter into a federation of peoples.”

Roughly the same time, on the other side of the ocean, thirteen former colonies of the British Empire were deciding whether to remain divided or to unite after the Declaration of Independence (1776). Supporters of the union reminded their citizens of how the European continent had set a bad example: the states in Europe were divided and had gone from one war to another, amidst endless atrocities and misery. And they drew the lesson from history that led them to opt for a federal union, the United States of America (Philadelphia Convention, 1787): “To look for a continuation of harmony between a number of independent unconnected sovereignties, situated in the same neighbourhood, would be to disregard the uniform course of human events, and to set at defiance the accumulated experience of ages.” (Alexander Hamilton,The Federalist). They took Kant’s teachings to heart.

We know that this idea is at the root of the process of European unification, which was inspired by the Ventotene Manifesto (“For a free and united Europe”), and is a fundamental goal of political action in our time, as Altiero Spinelli often recalled. It is said that the “new dividing line between progress and reaction” is between those who want to move beyond the absolute sovereignty of states, sharing it in some areas, in order to “create a solid international state”; and those who, on the contrary, want to preserve absolute sovereignty, often without realizing that this claim is purely ideological, and has no solid basis in reality.

The process of European unification, initiated by the Schuman Declaration of May 9, 1950, raised the problem of “institutionalized” peace as the starting point (A united Europe was not achieved: we had war), linking the construction of Europe to the goal of peace: “It proposes that production of coal and steel as a whole be placed under a common High Authority, within the framework of an organisation open to the participation of the other countries of Europe. The pooling of coal and steel production should immediately provide for the setting up of the common foundations for economic development as a first step in the federation of Europe and will change the destinies of those regions which have long been devoted to the manufacture of munitions of war, of which they have become the most constant victims.

…. .The solidarity in production thus established will make it plain that any war between France and Germany becomes not merely unthinkable, but materially impossible.” It was, therefore, at that precise moment that war became “unthinkable” in our countries, first for the Six “founding” member states and now for the Twenty-seven. Despite many flaws, this European Union has “disarmed” relations between the States. We can, therefore, say that Europe, governed by these institutions, now represents an area of “achieved peace” among its citizens. The message of Ventotene has brought European unification to life, and demonstrated that it is a constitutional process of a federal nature.

Europe and the World

What foreign policy should the European Union adopt today? The values that should inspire its action are inherent in its DNA: peace as the result of a system of supranational norms, sustainabilityas an economic-social model, and supranational democracy as the culmination of the historical development of citizenship. On what principles should a foreign policy capable of pursuing these values be based? Principles that, to be effective, must apply no longer only to Europe, but also to the world. This is a new principle that revolutionizes the traditional approach of the foreign policy of states which aim to increase the power of their own state to the detriment of others. We can, therefore, broadly formulate the following guiding principles for European foreign policy.

1) International security. The security of a state cannot be acquired by an enlargement of its sphere of influence, that is, with less security for others (I am safer if you are weaker). On the contrary, security must be mutual (I am safe if you are safe too). This principle must first be initiated in Europe, with the creation of the “common European home” (Gorbachev) as an alternative to the Putin regime’s policy of aggression. If this principle takes hold in Europe, then it can take hold elsewhere.

2) Interdependence among states. Under the system of absolute sovereignty, a state’s independence is assured by its strength. Interdependence, on the other hand, aims to enable states to find the right balance between autonomy and the achievement of common shared goals. With the ECSC, for example, interdependence between France, Germany and the other states was achieved through the creation of a High Authority that jointly managed the production and distribution of resources. So, interdependence and security for all. A similar solution could be pursued in the Middle East[5] and for the ‘governance’ of global public goods. This will lead to the primacy of universal law over that of the individual state, just as European law has primacy in Europe.

3) Multilateralism. This is the natural development of the policy of enlargement. Europe’s borders have never been defined, because the process of unity does not aim to create a “bordered” state, but to seek shared security with neighbouring states through common supranational institutions. What we call “borders” (limes) are actually “thresholds” (limen), which allow us to imagine relations between different areas of the world as open federations.

4) Regulatory power, that is, the EU’s capacity to produce rules. It has been doing this for seventy years, bringing together its citizens with rules in the fields of consumption, trade, transport, environmental protection, human rights etc. The EU is a “powerhouse” in this area; no other country in the world has developed a similar process. The European rules-based culture will come into its own when it becomes clear that “global public goods” cannot be governed by the force of individual states such as China, the US or others.

Based on these principles it will be possible: (a) to transform NATO into an equal partnership, a condition that would also be a guarantee (for Russia) that the end of the war in Ukraine will not result in the strengthening of American power in Europe, rather in the emergence of a truly autonomous Europe; (b) to base the “new world order” on a multilateral system with several pillars (U.S., EU, China, Russia, India, Latin America, Africa), rather than on powers vying for hegemony; (c) to reform the UN, by opening the Security Council to all major areas of the world and eliminating the power of veto in the Security Council, making way for the emergence of a world parliament.

EU foreign policy will thus be geared to reproducing the principle of federal unity, the basis of its initial political project, on a global scale.

Antonio Longo

[1] The reference is to a text published by “La Fondation pour l’innovation politique” – Fondapol.org on 2/3/2022, entitled “La Russie n’a pas seulement défié l’Occident, elle a montré que l’ère de la domination occidentale mondiale peut être considérée comme complètement et définitivement révolue.” This is a translation of an article that appeared on 26/2/2022 in the Russian RIA Novosti news agency (later removed), under the title “Russia’s advent and the new world order.” This article describes the imperialist project conceived by Putin: the total russification of Ukraine and Belarus as the starting point of a recomposition of a new world order that would undermine the West.

[2] Sovereignty is a very old term that refers to the idea of a single and indivisible centre of power in a state. The global challenges of our time, however, demonstrate two things. The first is that states (not even the largest) are no longer truly “sovereign,” since they can no longer solve problems alone; they are forced to cooperate in one way or another. The second is that the “capacity to act” of states (another old definition of sovereignty) lies not so much in taking decisions (making laws etc) or making choices, but in “the ability to control the outcome of what you have decided” (as Mario Draghi says). Otherwise, you are not actually “sovereign”. Now, in the context of the enormous challenges facing humanity, this “ability to control” can only exist in a situation of maximum interdependence between states, that is, at the world (federal) level. This means that with federalism it is possible to control the use of power, this is no longer true with national sovereignty.

[3] Because of the radical opposition of principles in the field, the outcome of the Ukrainian conflict may have two possible alternative conclusions: 1) negotiations over the partitioning of the occupied territories: in this case, it will be clear that aggression paid off in the end. This would be a victory of the principle of “absolute” state sovereignty and, a defeat of the principle of “relative” sovereignty, at the basis of European unity; 2) the implosion/defeat of the current regime in Moscow (as a result of facts unimaginable today) and the agreement by a new Russia to become part of a security system in Europe, governed by common institutions.

[4] Immanuel Kant, Idea for a Universal History from a Cosmopolitan Point of View, Thesis VII, 1784.

[5] For the reasons given above, the “two peoples two states” formula reproduces the model of states which are completely sovereign (to wage war on each other), unless a strong federal constraint (a shared government for security purposes) is created. The ECSC model seems the most realistic, with the creation of a “Middle East Economic Community for Water and Energy” between Israel, Jordan and other interested countries: it would be this (institutionalized) community of interests that would guarantee peace for all states and peoples concerned, including the Palestinians.