Nationalism and pacifism: a critical mix (*)

1945. George Orwell.

Nationalism. Multiculturalism. Cosmopolitanism.

NATIONALIST FEELING

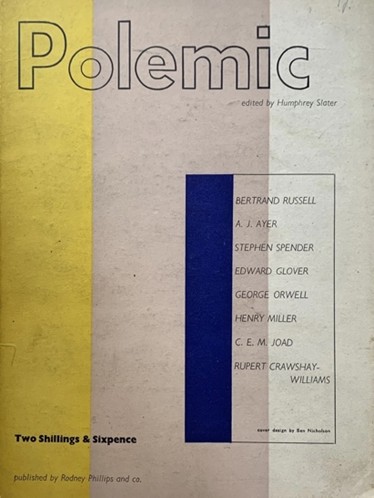

In October 1945 George Orwell published an article, Notes on Nationalism in Polemic: A Magazine of Philosophy, Psychology & Aesthetics. (Fig. 1)

Fig. 1 The publication Polemic: A Magazine of Philosophy, Psychology & Aesthetics. 1945

Immediately afterwards, Penguin Books included the article in a book.(Orwell, 2018)

The book had a specific, circumscribed aim: to analyse nationalist feeling among English intellectuals during the Second Word War.

It struck me that this notion of nationalist “feeling” might be useful in an attempt to understand the current positions of western intellectuals, particularly in Universities, regarding the current wars and multiculturalism.

Orwell is at pains to point out how many English and western intellectuals adopted critical or openly anti-western stances before and during the Second World War.

After the Russian attack on Ukraine, we seem to be living in a period that has some similarities with 1938, so much so that Orwell’s book may be particularly relevant today.

For Orwell “nationalism” is a feeling that may refer to a nation, an ethnicity, a geographical area, a religion or a social class.

“By ‘nationalism’ I mean first of all the habit of assuming that human beings can be classified like insects and that whole blocks of millions or tens of millions of people can be confidently labelled ‘good’ or ‘bad’. But secondly – and this is much more important – I mean the habit of identifying oneself with a single nation or other unit, placing it beyond good and evil and recognizing no other duty than that of advancing its interests. Nationalism is not to be confused with patriotism. Both words are normally used in so vague a way that any definition is liable to be challenged, but one must draw a distinction between them, since two different and even opposing ideas are involved. By ‘patriotism’ I mean devotion to a particular place and a particular way of life, which one believes to be the best in the world but has no wish to force on other people. Patriotism is of its nature defensive, both militarily and culturally.

Nationalism, on the other hand, is inseparable from the desire for power. The abiding purpose of every nationalist is to secure more power and more prestige, not for himself but for the nation or other unit in which he has chosen to sink his own individuality. (Orwell, 2018).

According to Orwell nationalist thinking is obsessive, unstable and indifferent to reality. and tendencies such as communism, political Catholicism, Zionism, antisemitism, Trotskyism and Pacifism.

It can be divided roughly into three categories. Positive, Negative or Transferred Nationalism.

Positive for Orwell are patriotic, non-aggressive forms of nationalism serving one’s own interests, such as Celtic (Irish, Welsh) nationalism, unlike Anglophobic forms of nationalism which he regards as Negative.

For my purposes, Transferred Nationalism is the most interesting of the three, since Orwell suggests that nationalist feeling can move away from one’s own country to another.

“In societies such as ours, it is unusual for anyone describable as an intellectual to feel a very deep attachment to his own country. Public opinion – that is, the section of public opinion of which he as an intellectual is aware – will not allow him to do so. Most of the people surrounding him are sceptical and disaffected, and he may adopt the same attitude from imitativeness or sheer cowardice: in that case he will have abandoned the form of nationalism that lies nearest to hand without getting any closer to a genuinely internationalist outlook. He still feels the need for a Fatherland, and it is natural to look for one somewhere abroad. Having found it, he can wallow unrestrainedly in exactly those emotions from which he believes that he has emancipated himself. God, the King, the Empire, the Union Jack – all the overthrown idols can reappear under different names, and because they are not recognized for what they are they can be worshipped with a good conscience. Transferred nationalism, like the use of scapegoats, is a way of attaining salvation without altering one’s conduct.” (Orwell, 2018).

Orwell sees examples of Transferred Nationalism in Communism, political Catholicism, racism, class prejudice and pacifism. In particular, his view of pacifism as Transferred Nationalism strikes me as astonishingly relevant today.“Pacifism. The majority of pacifists either belong to obscure religious sects or are simply humanitarians who object to the taking of life and prefer not to follow their thoughts beyond that point. But there is a minority of intellectual pacifists whose real though unadmitted motive appears to be hatred of western democracy and admiration of totalitarianism. Pacifist propaganda usually boils down to saying that one side is as bad as the other, but if one looks closely at the writings of younger intellectual pacifists, one finds that they do not by any means express impartial disapproval but are directed almost entirely against Britain and the United States. Moreover, they do not as a rule condemn violence as such, but only violence used in defence of the western countries. The Russians, unlike the British, are not blamed for defending themselves by warlike means, and indeed all pacifist propaganda of this type avoids mention of Russia or China. It is not claimed, again, that the Indians should abjure violence in their struggle against the British. Pacifist literature abounds with equivocal remarks which, if they mean anything, appear to mean that statesmen of the type of Hitler are preferable to those of the type of Churchill, and that violence is perhaps excusable if it is violent enough. After the fall of France, the French pacifists, faced by a real choice which their English colleagues have not had to make, mostly went over to the Nazis, and in England there appears to have been some small overlap of membership between the Peace Pledge Union and the Blackshirts. Pacifist writers have written in praise of Carlyle, one of the intellectual fathers of Fascism. All in all, it is difficult not to feel that pacifism, as it appears among a section of the intelligentsia, is secretly inspired by an admiration for power and successful cruelty. The mistake was made of pinning this emotion to Hitler, but it could easily be retransferred.” (Orwell, 2018).

MULTICULTURALISM AND MASOCHISTIC NATIONALISM

In the international debate I have not found significant references to Orwell’s article. The sole exceptions are two books by Göran Adamson, considered, like Orwell, a “leftwing liberal”. He cites Orwell profusely in his first book, which analyzes the approach of Swedish Universities to diversity and multiculturalism (“A Trojan Horse. A Leftist Critique of Multiculturalism in the West”, Adamson, 2017). In his second book (Adamson, 2021), he uses the term “Masochistic Nationalism” (or “Self-critical Nationalism”) to describe the anti-western stances of many “leftist” intellectuals, whilst confining to the “Right” the traditional notion of Sovereigntist Nationalism (Adamson, 2021).

Adamson sees Masochistic Nationalism or Self-critical Nationalism as fairly widespread in the non-liberal left which, in recent years, has extolled diversity and multiculturalism. He links this to the Transferred Nationalism Orwell attributed to English intellectuals.

A focus on diversity – for different but mutually reinforcing reasons – is a common trait of the Masochist/Self-Critical Left and the Nationalist Right. For the Right, it serves the purpose of demanding separation, in order to maintain one’s own culture, income and so on. The Left seeks to help the weak, disadvantaged and persecuted, but its acritical exaltation of multiculturalism risks considering individuals of a given ethnicity merely as members of a group, undermining the liberal model of individual freedom.

In the preface to his book, “A Trojan Horse”, Adamson writes:

“Multiculturalism is a conservative idea, which is seen as progressive. Multiculturalism and diversity are about background, ethnicity, belonging, spokespersons and roots. Those who talk about roots talk about an idyll of the past, a historical Eldorado in contrast to universal suffrage, technological progress, and everything else that belongs to modern society.

….

Critiques against diversity, we are told, come from the right. This book takes the opposite position. Convincing criticism against diversity always comes from a leftist perspective, from those who advocate meritocracy instead of group rights, majority and democracy instead of adoration of minorities, equality between men and women instead of patriarchy, the rule of law instead of ‘minority legislation’, science instead of belief, debate instead of censorship, modernity and the bliss of forgetting instead of an obsession with historical injustice

……….

Moreover, the ideology of diversity shows numerous similarities with neoliberalism. Neoliberalism profits from diversity, and diversity comes in handy to the neoliberals. The Swedish establishment has allowed a Trojan horse into its midst. (Adamson, 2017)

Adamson comes to these conclusions after analyzing the result of the Swedish government project Diversity at the University, funding Universities that promote diversity in the academic world.

His concern is that structural justice (or injustice) can produce benefits or disadvantages for groups, contradicting the mission of the Universities themselves.

Universities need to promote the freedom and equality of individuals, not groups.

As a result of the model of structural justice, group identity is seen as more important than individual choice. Due to the ideology of diversity, criticizing minority groups, previously perceived as vulnerable, is deemed improper.

If Universities are asked to affirm the value of diversity when enrolling students, their role is put into question.

By idealizing vulnerable groups, individuals who do not agree with the group are abandoned to themselves.

It is useful to compare Adamson’s view with that of Kenan Malik, in his book Multiculturalism and its Discontents: Rethinking Diversity after 9/11 (Manifestos for the 21st Century).

“What is striking is that many of the arguments of right-wing critics of multiculturalism, who refer to the thesis of the clash of civilizations, are similar to those of the supporters of multiculturalism. ….

Behind the hostility, however, the two sides share the basic assumptions about the nature of culture, identity and difference. Both consider the main social divisions as the result of a cultural or civilizational matrix. Both see cultures, or civilizations, as homogeneous entities. Both insist on the crucial importance of cultural identity and the preservation of this identity. Both perceive conflicts that emerge from non-negotiable values as unsolvable. (Malik, 2016).

COSMOPOLITANISM

In the current debate on peace and the ongoing wars it seems to me that what is lacking is any indication of a path that may concretely lead to a reduction in conflicts. There is no mention of a cosmopolitan prospect for the human race, i.e. the Planetary Man of Ernesto Balducci.

Cosmopolitanism suggests that, needs must, men should be citizens of the world, overcoming the social and political differences between states and nations.

If not cosmopolitanism, what other solution exists for the future of mankind in the Anthropocene? (Montani, 2022).

According to Federalists, nation states (or empires) are not the only way to organize human society. Nationalism is born when the state – freeing itself of the power previously exercised by the Church and/or the Empire, and becoming “absolutely sovereign” (the Westphalian system) – needs to base its legitimacy on a new entity: the nation. Historically, this was made forcefully clear by the French revolution when, overnight, the King’s subjects, previously Alsatians, Bretons, Occitan speakers and so on, became the “French”. They used to fight and die for the King; now they fought and died for the “French nation”. Nationalism is therefore the ideology of the bureaucratic, centralized nation state (Albertini, 1997).

The process of European unification shows that states and nations previously at war over many centuries can come together, an improvement not only in terms of peace but also economically, socially and for human rights.

Although the successful model of European unification, described in this issue by Antonio Longo, indicates the past and future path for its cosmopolitan construction, its originality and potential are underestimated.

Opponents of European unification include not only sovereigntists but, paradoxically, the proponents of multiculturalism, self-critical of a “European Homeland”. Due to the ongoing process of European construction, European patriotism cannot become nationalism. The federal model balances the power of the state with that of a supranational government, respecting nations and European cultures.

The powers, large and small, of the state, as well as economic and religious powers do not seem to understand the risks their increasingly aggressive attitude involves.

Peace and Cosmopolitanism may be imposed by Nature, climate and environmental risks that may force human beings to cooperate to the benefit of all.

Mitigating global warming is a common aim that can be achieved solely by controlling greenhouse gas emissions. Adapting to global warming, on the other hand, could cause even more catastrophic conflicts if faced with a nationalist logic.

Meanwhile, climate change is causing conflict. The consequences of drought in Syria in 2006-2009 were considered one of the leading causes of the civil war. A detailed and accurate report by Imperial College (F. Otto et al, 2023) attributes the early century drought to climate change and warns of a disastrous climate future for the Middle East.

Longo’s proposed “Middle-eastern economic community for water and energy” including Israel, Jordan and other willing countries could kick off a process similar to that of the European Coal and Steel Community, the first step in the peace process in Europe and in the prosperity of Europeans. Based on its experience, a Federal Europe could help this collaboration.

When shared, scientific and technological research helps to face the challenge of the environmental crisis and energy transition. In this issue, Tommaso Pacetti indicates the forms of cooperation that are possible in order to overcome water shortage and other environmental emergencies, fostering a process of sharing and non-conflictual relations.

Luciano Ipsaro Palesi and Paola Zamperlin take on the subject of Artificial Intelligence, highlighting the risks, its potential, and the ongoing conflicts.

It should be noted that the European Union is already recognized internationally for its positive role in the climate debate and for the need to control Artificial Intelligence, as shown by the albeit modest results of the Dubai Climate Conference in 2023 and the regulations governing the use of AI recently introduced by the EU.

The federal approach which brought about peace in Europe is often forgotten and, with it, the dream of a United States of Europe. Yet, Federalism is the best hope of defeating the nationalism of states, organizations and people, enabling a non-aggressive form of patriotism in communities and nations.

George Orwell too believed in the European Federation:

“In March 1945, in Paris, in a now liberated Europe, Altiero Spinelli organized a conference with Albert Camus, Emmanuel Mounier, André Philip, George Orwell and others, in which a Provisional Committee for the European Federation was approved.” (Spinelli, 2023, from the Preface by Guido Montani).

REFERENCES

G. Adamson, The Trojan Horse: A Leftist Critique of Multiculturalism in the West, Post-Diversity Press, 2017.

G. Adamson, Masochistic Nationalism: Multicultural Self-Hatred and the Infatuation with the Exotic, Routledge Studies in Political Sociology, 2021.

M. Albertini, Lo Stato nazionale, Il Mulino,1997

L. A. Ipsaro Palesi, P. Zamperlin, Intelligenza Artificiale e conflitti, Testimonianze, n. 555-556, 2024.

A. Longo, La guerra, la pace e l’ordine mondiale, Testimonianze, n. 555-556, 2024.

K. Malik, Il multiculturalismo e i suoi critici. Ripensare la diversità dopo l’11 settembre. Unione degli Atei e degli Agnostici Razionalisti – UAAR-, 2016.

G. Montani, Antropocene, Nazionalismo e Cosmopolitismo – Prospettive per i cittadini del Mondo. Mimesis, 2022.

G. Orwell, Notes on Nationalism, Penguin Random House, 2018.

F. Otto et al, Human-induced climate change compounded by socio-economic water stressors increased severity of drought in Syria, Iraq and Iran, Imperial College, 2023.

T. Pacetti, Gestire le risorse idriche per costruire un futuro di pace, Testimonianze, n. 555-556, 2024.

A. Spinelli, La mia battaglia per un’Europa diversa, Edited by Guido Montani, Edizioni Società Aperta, 2023.

(*) The Italian version of this text was published in the Rivista Testimonianze, NN. 555 – 556. (https://www.testimonianzeonline.com/2024/11/nn-555-556-the-age-of-global-citizens/)