*A partnership The Ventotene Lighthouse / Eurobull

Italian version at https://www.eurobull.it/essere-giovani-in-europa-quale-futuro?lang=fr

The world is changing, visibly and dramatically. The floods which hit Central Europe in July – the last in a long series of disasters – glaringly highlighted the unpredictable consequences of climate change, which is now giving rise to increasingly perilous, abrupt and chaotic meteorological phenomena.

The situation appears to be constantly escalating. The climate system is at breaking point and any efforts being made to address the situation tend to feel like attempting to bail out a sinking ship: the water is pouring in faster than we can empty it.

The world is changing, and this is nothing new. But a rational, strategic approach to climate change, based on a long-term vision of the future, would be entirely new. Those who will have to live with the consequences of climate change are not the past generation, those who enjoyed the so-called “Economic Boom”, or those – in Europe and North America – who reaped the benefits of it during the 60s and the 70s. The new generations are those which will be trapped by the consequences of politics focused on an eternal present, and lacking the imagination to face the future.

The youngest generations, and those as yet unborn, will be living in a more and more urbanized world, with rising temperatures and without the necessary resources for their survival. These young people will need to be able to count on new political, social and economic structures, and innovative institutional systems, to tackle challenges that will otherwise be insurmountable.

The process of European unification arose and developed around the idea of ushering in a new era of peace, after the horrors of the two World Wars. But this idea is no longer enough: the Union now has to take responsibility, and it is a huge responsibility, for building a new and different future for its younger generations. And not just for them alone, because the challenges involved go beyond continental and national borders. The European Union seems better equipped than other political players to bring a considerable number of industrialized nations into line with the new principles of sustainable development – in both economic and ecological terms.

But do young people trust the European Union? As an institution it is often viewed as a distant, bureaucratic body. An organization that issues diktats from the glass palaces of Brussels, and sometimes appears to be uncertain of its identity. The recent COVID pandemic has highlighted its cracks, flaws and slow response times.

Brexit placed a heavy toll on the unity of the EU, but did not lead to the break down envisaged by the opponents of the integration process. At the same time, the attitude of Poland and Hungary towards the “rule of law” represents a new challenge to the primacy of European law over national systems.

But if the European Union has to answer to anyone in particular, that must necessarily be its younger inhabitants. We thought it would be useful to take a little survey, with the limited means at our disposal, to explore how young Italians – with or without experience of living in the rest of Europe – feel about the EU, this institution that increasingly appears to be viewed as vital to building a better future for everyone.

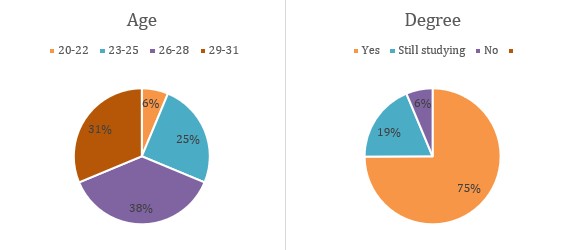

Ours was not an exhaustive sample. We prepared a set of questions which we then sent to various young people, and we were able to extrapolate some considerations from their responses.

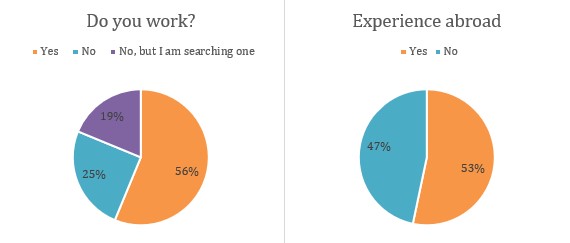

One of the most significant findings was the percentage of young people who state that they feel European – 50% of the sample – and those who confirm that it makes sense to feel European, 93.8%. If almost all respondents acknowledge that this sense of belonging is meaningful, and highlight its importance, why are some of them not feeling it?

From this perspective, the accounts of our respondents offer precious insights. Eleonora, 27, and with a degree in sociology, writes “I think the reason I don’t feel European is to do with the fact that I have never lived in another country”. Indeed all those who have lived abroad feel European. It goes without saying that when you cross a border, it is impossible not to perceive the existence of the European Union. Programmes like Erasmus have been essential in developing a common European sentiment among participants. But though it is a fundamental initiative that must be supported and promoted, it remains an opportunity that only a tiny minority of young people have access to.

So what stops young people from feeling European? We can summarize the answers provided in three main categories. Some respondents stated that the European Union does not really care about its citizens or does not care enough: some are sceptical about it being possible to bridge the gap between Brussels and their local area, and the third category comprises those who, while believing in the values expressed by the EU, find it hard to see actual results.

Despite these responses, even the doubters see the European Union as a source of hope: 81.3% of those surveyed see it as the organization best equipped to address the challenges and priorities of the present day. The remaining percentage ticked “I don’t know”. There is therefore hope, and a clear awareness that such issues can only be handled on a European level.

Our respondents also showed great interest in the policies that will affect their future. As is natural for this generation – destined by birth to take charge of the planet in the near future – the key issue, regardless of personal politics, remains what the future holds; how to achieve economic stability and how to respond to the major ecological, economic and social challenges we are currently facing.

In short, young people are calling for change. But the European Union is by no means unresponsive. Not incidentally, the goals that must be pursued by member states when using “Next Generation EU” funding are entirely in line with the priorities expressed by our respondents.

Young people’s differing stances towards the European Union are probably due to different constructions of meaning, contrary to what might be expected. For all under 30s, the EU is the container they live in, and create and live out their dreams and aspirations. More importantly, it is the container in which they will have to face the great challenges of the 21st century. There can be no discussions about the future without considering the European Union, without a discussion on its role, and undoubtedly without an EU capable of living up to young people’s expectations. Initiatives like “Next Generation EU” are clear signals in this direction. The EU is doing everything in its power to place the younger generations at the centre of the political agenda.

At this point, maybe we should be asking ourselves what nation-states should be doing: sharing more of their sovereignty with the Union and endowing it with a broader scope for action, given that young people see it as the institution best equipped to tackle the challenges of the future, with the capacity and the tools to respond to them?

The EU’s problems remain, in any case. Programmes like Erasmus, for example, often feel like they are destined only for the privileged few: those who can afford to go to university, in the first place and, in addition, can afford to live abroad, considering that the grants offered are rarely enough to cover all of students’ living expenses.

On one hand, therefore, the European Union is seen as a potential resource for facing the challenges of the future, but on the other it is viewed as a distant world, part of a different system. This gap needs to be bridged in order to capture the existing needs of the new generations; there are already some potential solutions on the table but these are yet to be implemented.

It is certainly not the first time that young people have represented both a challenge and an asset for the European integration process. Tools like the European Social Fund, Interreg, and the European Structural and Investment Funds, as well as NGEU, have directed community efforts toward some of these challenges, including young people in considerable investments of resources. This is surely promising, though shortcomings remain in terms of communication.

Tools and programmes like those mentioned above are a step in the right direction, but to ensure that young people feel European, they not only need to be able to see Europe as a major federal political community, but also to guarantee that European institutions become an ally to tackle unemployment, the generational socio-economic gap, the ecological and climate crisis, and the very question of political representation.

What emerged from these interviews was the idea that a common future exists for the European “community”. A common future which is also the solution to the lack of political credibility currently affecting many national institutions.